Will Marshall and Robbie Schingler have never shied away from vocalizing their view of Planet as a natural consolidator in earth observation. They haven’t been afraid to act on that view either, completing six acquisitions in the last eight years including three in the last two years.

But is there any merit to that view? And if so, why?

1. Blackbridge (September 2015)

Planet’s first acquisition came midway through its constellation build-out. With over 80 satellites launched (and more lost due to launch explosions), the company already operated the largest earth observation constellation in history. However, it lacked distribution and an archive capable of supporting basic time series analytics — a requirement to open up the commercial market.

The Blackbridge deal was a step toward solving these problems. It owned and operated RapidEye, a constellation of five satellites that had been in operation for over six years and amassed an archive of over six billion square kilometers at 5m resolution.

The acquisition added a second in-orbit asset collecting daily data. It also brought over 100 customers and a truly global footprint; while Planet’s customers (at the time) were largely concentrated in North America and Asia, Blackbridge had a strong foothold in Europe and to a lesser extent, Latin America.

Blackbridge’s rationale appears straightforward. The business had experienced its share of trials (RapidEye having been purchased out of bankruptcy in 2011), and Planet shared the same vision, with a better plan of execution.

CEO Ryan Johnson foresaw the success of Planet’s strategy in his open letter announcing the deal:

We believe in the agile aerospace strategy that Planet Labs has developed and that it will provide our company a long-term strategic advantage.

We have been exploring solutions for RapidEye+ for almost a year now and have completed a Phase A study engaging multiple large aerospace companies to provide a solution. During these investigations, there was no solution that provided a clear and compelling competitive advantage compared to our traditional competitors, until we met Planet Labs.

It wasn't until I met with the Planet Labs team, in person, in their San Francisco headquarters and they walked me through their strategy, capabilities, and technology road map that I realized that this was a company that had a unique different set of capabilities. I believe that these capabilities will position our company differently and help us create a long-term strategic advantage.

This agile aerospace approach will allow them to launch hundreds of satellites over the next two years, providing daily imaging of the entire planet and rapidly introduce new capabilities like multispectral channels and enhanced resolutions faster and more cost effectively than we could bring similar capabilities to market with a traditional aerospace program.

The deal accelerated a common mission: to unlock the power of geospatial data for decision makers everywhere. This concept of accelerating a shared vision is important; it persists across all of Planet’s acquisitions.

The terms of the deal were never disclosed, but the price is unlikely to have been too onerous. Blackbridge had purchased the constellation four years earlier for ~13 million euros, and Johnson noted how they were looking for Planet just as much as Planet was looking for them.

The RapidEye constellation remained in operation until April 2020.

2. Terra Bella (April 2017)

Terra Bella was a significant transaction for a relatively young company.

Terra Bella had been one of the first major success stories in commercial earth observation, having been acquired by Google for $500 million in 2014 (it was Skybox Imaging at that time). Yet just three years later, Planet took control.

For Planet, the deal added a high-resolution constellation to pair with its medium-resolution, wide area scan. It birthed the unique “tip and cue” model for monitoring global change and brought over a talented team experienced in the agile aerospace philosophy of rapid prototyping and iteration.

For Google/Terra Bella, the rationale again seems straightforward: the two companies were after the same mission. Co-founder John Fenwick said:

From the start, Planet and Terra Bella have shared similar visions and approached aerospace technology from a like-minded position, and while our on-orbit assets and data are different, together we bring unique and valuable capabilities to users. Planet and Terra Bella together enables the continuation of our mission and makes for an ever-stronger business.

But it’s not just an aligned vision that played a key role. Ashlee Vance notes in When the Heavens Went on Sale that Marshall’s friendship with Sergey Brin ultimately played a key role in convincing him to part ways with Terra Bella.

For his part, Brin — at Marshall’s urging — likely saw how the two would be worth substantially more together over the long run. Planet’s transition to Google Cloud hosting a few months prior likely didn’t hurt; nor did the agreement for Google to continue buying SkySat data.

The purchase was a stock transaction, and Google continues to hold a 12.5% stake in Planet more than six years later.

3. Boundless Spatial (March 2019)

Boundless was Planet’s first acquisition outside of the in-orbit realm. Having completed Mission One in late 2017, its attention turned from space assets to software capabilities. The data was only so valuable if it wasn’t accessible.

The deal offered two things: (1) a suite of geospatial tools and software to enable Planet to deliver its data to the web; and (2) a strong foundation for government work (via an existing NGA contract and badged employees). Immediately after closing, the Boundless team formed Planet Federal, a subsidiary focused on U.S. government contracts.

Once again, the transaction’s value for Boundless lay in Planet’s ability to accelerate its vision of “unlocking the full value of location-based data for all.” Schingler outlined the effect:

At Planet, we come at it from the space side and the data side. Boundless creates software and tools to allow people to consume geospatial data in the cloud and on the web. Bringing these things together will help users get the most value out of the vast amount of geospatial data we are developing.

The original purchase price was $40 million. Post-closing, however, a fuss over “information concerning material customer contracts” led to a reduction in the price to $16 million. It’s unclear exactly what this related to (the NGA contract was well documented publicly), but it ended up working in Planet’s favor.

4. VanderSat (December 2021)

VanderSat provided the foundation for building out Planetary Variables (“PVs”). Specifically, the acquisition produced three PVs: Soil Water Content, Land Surface Temperature, and Biomass Proxy.

PVs transform raw satellite imagery into generic, intuitive information products that anyone familiar with Excel can manipulate (as opposed to the geospatial experts who must navigate the raw data). PVs expand the number of possible users of Planet data and are an important move “up the stack.” Customers use these PVs as building blocks to create products and services, resulting in a sticky relationship.

For example, SwissRe and AXA use Soil Water Content to price parametric drought insurance in more than 20 countries. Using the PV, the insurers can assess the history of soil water levels in a particular area over a long period of time and monitor differences on an ongoing basis, automatically determining when a payout is due. This level of automation reduces the insurer’s operational burden and helps the farmer get paid quickly.

This example also demonstrates the power of Planet’s archive. Without the historical precedent, it would be impossible to accurately determine pricing and payout levels. No other company has data on every field in the world going back 6+ years.

Speaking on the TerraWatch Space podcast about how the acquisition came about, Thijs van Leeuwen, VanderSat CEO, shared:

I would say we fell in love. We started to work together in a partnership, and they opened up their data, we opened up our data, and we could actually see the value of joining forces… We were building products, but by leveraging their data, we could build even more unique products that could open up new use cases and new markets.

And at the time of acquisition, van Leeuwen stated:

VanderSat is a mission-driven company with the goal to serve one billion hectares of land in 2024. By joining Planet, our mission and impact will be dramatically accelerated and together, we aim to reach that goal in 2022.

Once again, we see Planet’s ability to accelerate the missions of those in its surrounding ecosystem create the circumstances for acquisition. The cultural fit is a natural byproduct of an aligned vision and an urgency of action.

The redundancy of Planet’s constellation also eliminates a key vulnerability for downstream providers such as VanderSat (and Salo Sciences), many of whom rely on public datasets. When public satellites go down, the downstream providers can’t operate; Planet’s constellation builds in redundancy that allows it to continue uninterrupted service even if several satellites fail.

5. Salo Sciences (January 2023)

Salo Sciences is, in effect, a carbon copy of VanderSat, except focused on downstream forestry products instead of agriculture/insurance. Planet had partnered with the company since 2019 and knew the team well.

The Salo acquisition is set to produce three more PVs: Forest Carbon, Forest Structure, and Vegetation Encroachment. Though not available via API until later this year, they have already led to some meaningful contract wins.

PG&E, for instance, signed a seven-figure contract for Vegetation Encroachment to monitor its entire transmission grid, over 160,000 line kilometers. The potential for like contracts is notable, with more than 1,000 public utilities located in the U.S. alone.

Planet also recently unveiled pricing for its Forest Carbon dataset, which begins as low as $0.10 per hectare. This public pricing transparency is a meaningful step forward for earth observation data and contributes to greater accessibility.

Again, the catalyst for the transaction was Planet’s ability to accelerate Salo Sciences’ mission. Co-founder and CEO Dr. David Marvin said:

Salo Sciences was founded to help implement and scale nature-based solutions to climate change. There is no better way for us to accelerate that mission than joining forces with Planet to launch a next-generation system to monitor the carbon stocks and health of every tree on Earth.

6. Sinergise (August 2023)

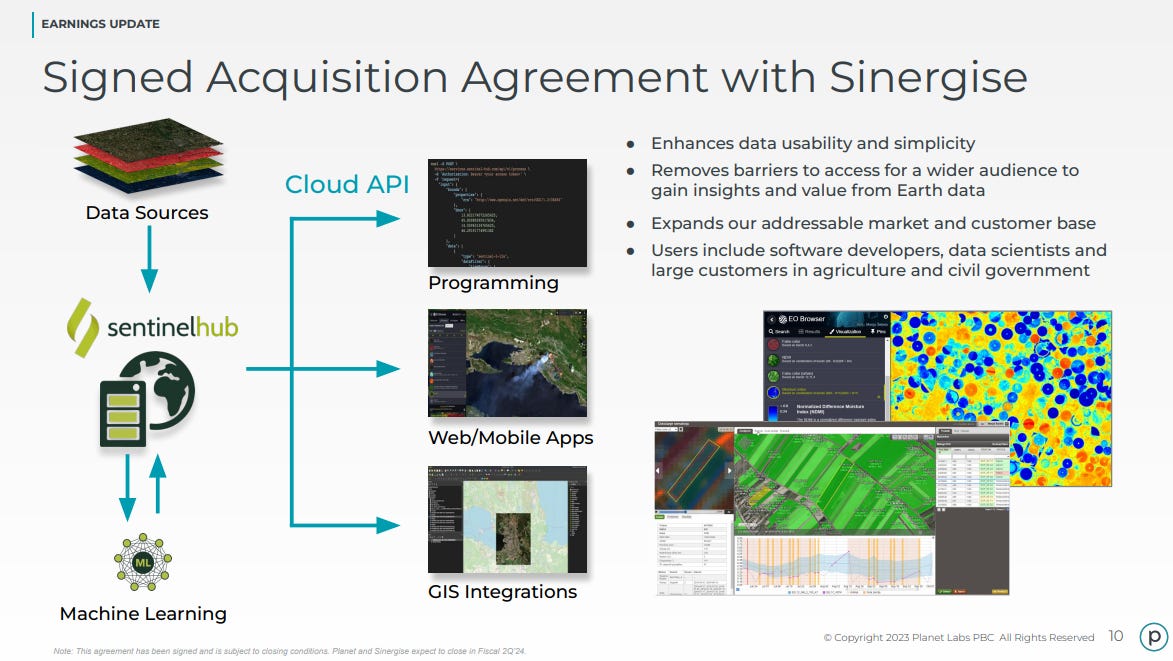

Sinergise is, in my opinion, the most interesting acquisition to date. Its Sentinel Hub platform is deeply embedded in the earth observation community and used by tens of thousands of users to access and analyze satellite data from a variety of public and private sources.

I won’t waste too much time explaining the transaction as Planet’s Q4 presentation details the benefits quite well.

It makes Planet’s data more widely accessible, easier to analyze, and easier to combine with other data sources. In practice, this translates into a significantly easier process to build applications on top of the data. The platform also brings a team of 80 or so software engineers and a sizable developer ecosystem.

Notably, Sinergise is profitable and had been working with Planet since 2016; they did not have to pursue this deal. But I bet you can guess why they did: Planet could accelerate their vision.

Grega Milcinski, co-founder and CEO of Sinergise, penned an open letter elaborating on the rationale. The executive summary follows:

Why? Because time is of the essence, and we are late!

Why Planet? They are really good at what they do, and there is a good fit with what we do.

How will it impact our users? In a word: acceleration, with faster updates and additional solutions

What does it mean for Europe? More investment, an expanded presence, and jobs

Will we continue working on open data? Of course! With Planet, we are highly focused on the impact that EO can have on our lives and open data is a very important part of it.

This acquisition could be the starting point for an Earth data platform capable of reaching “every business and every government in the world,” a point Marshall and Schingler frequently reference as their goal — but I’ll save that type of world-changing prophesying for another write-up.

For now, it’s a great step forward in expanding the accessibility of Planet data.

Conclusion

Building a new market takes quite a bit of time, money, and talent. Combining forces is often more effective than blazing a path alone — especially in space.

These deals have yet to generate a meaningful ROI in dollar terms (Planet remains significantly unprofitable), but they have certainly driven incremental improvements that will reduce the time it takes to build out the market. They have also served as an invaluable source of specialized talent acquisition in an undersupplied market.

The largest companies are often born from the simplest visions. The simplicity and clarity of Planet’s vision — together with its capacity for execution — is precisely what positions it as a consolidator. What company in earth observation is not after the same goal as Planet? And more importantly, what company would not benefit from greater access to Planet data?

Acquisitions are likely to continue to play an integral role in Planet’s evolution into a much larger company over the next decade.

Tags: PL 0.00%↑